Delocalized electrons, esoteric symbols, and the periphery of knowing.

How a sleeping mind saw what reason couldn’t: the ring that reshaped chemistry.

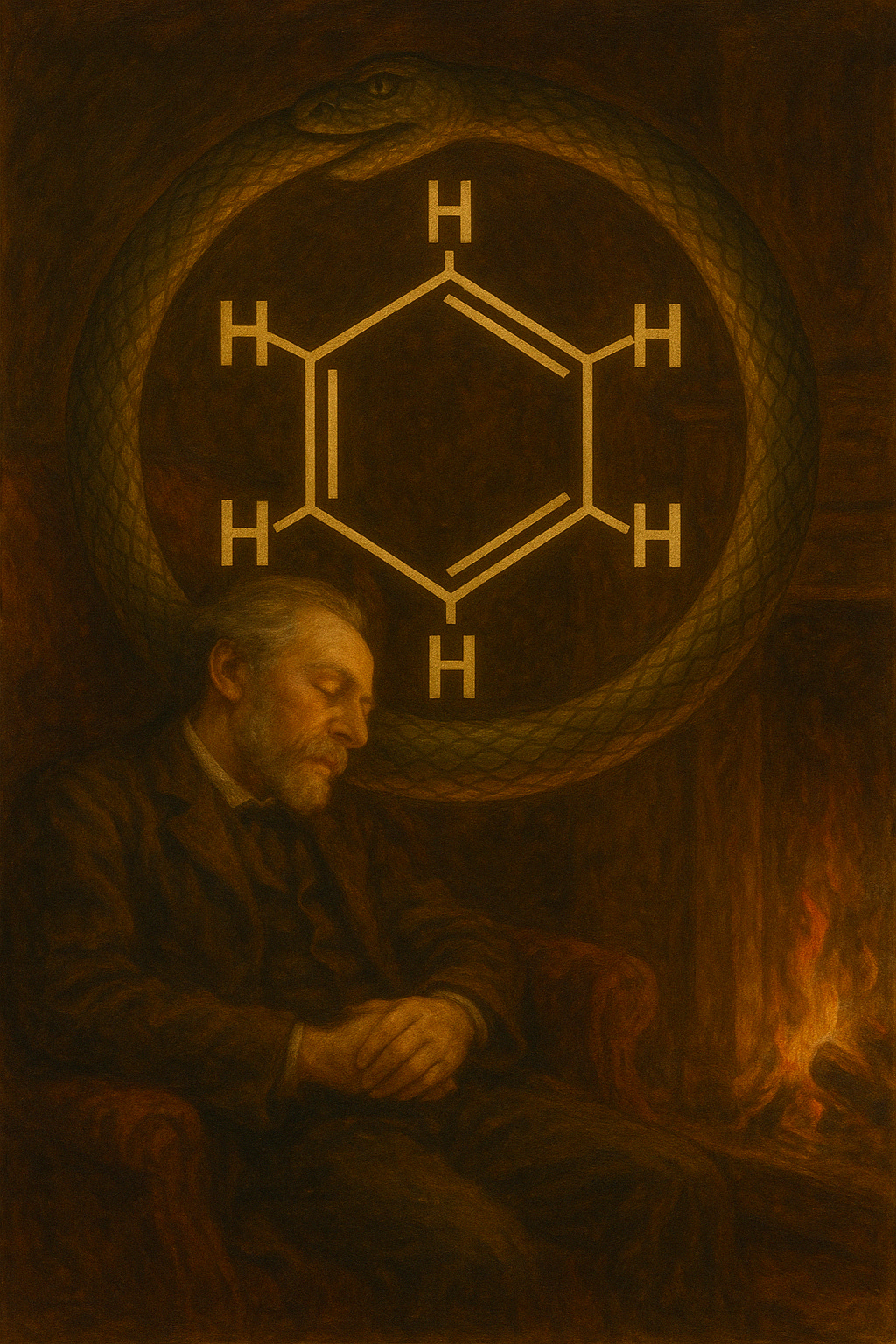

Imagination is an overlooked aspect of scientific work. We owe the structure of the benzene ring to a far‑out vision by a German chemist in 1865. His name was August Kekulé. The insight arrived not at the bench, but through a nap by his fireplace.

Chemists in Kekulé’s day believed organic molecules formed linear or branched chains. They expected benzene to fit neatly into these existing theories. But Kekulé’s experimental observations didn't match those assumptions. While linear or branched molecules were typically reactive, benzene was exceptionally stable, resisting reactions common to these known structures.

One winter evening he dozed beside the fire. In that half‑sleep the flames turned into a snake coiled on itself, biting its tail. No beginning. No end. The name for this symbol is the Ouroboros—an image found in mysticism, esoterica, and the tombs of pharaohs. In benzene, electrons flow continuously around a 6-membered carbon ring, evenly sharing their energy and giving the molecule its unique stability. The Ouroboros and benzene both represent cycles that sustain themselves—endings feeding beginnings. Beginnings unravelling into endings. The boundaries blur together as if one unified, pulsating, vibrating whole

Years later, at a scientific celebration in Berlin marking the 25th anniversary of his discovery called Benzolfest, Kekulé recounted the dream and advised:

“Let us learn to dream, gentlemen, and then perhaps we shall learn the truth.”

He immediately followed with but one caveat . . .

“But let us beware of publishing our dreams until they have been tested by waking understanding.”

He is, after all, still a scientist.

Excellent article interesting